A New Era for the Ampere

Metrologists are conservative by nature, knowing that the premature adoption of a new measurement standard could lead to confusion in both science and commerce. So it is a big deal that the International System of Units (SI) is poised to undergo its first major overhaul since its birth in 1960. Two years from now at the General Conference on Weights and Measures in Paris, officials will adopt a new SI in which every unit can be obtained from fixed values of several fundamental constants [1]. All eyes are on the kilogram, which will no longer be defined by the mass of a cylinder of platinum-iridium alloy that has been kept in a Parisian vault since it was fabricated in 1889. Somewhat overlooked, however, are advances in standards for electrical resistance and voltage, without which the new SI would not be possible. A new report [2] from Wilfrid Poirier and colleagues at France’s metrology and testing laboratory, LNE, puts these electrical standards in the spotlight by combining them to create a current source based on the electron charge (as opposed to Ampère’s law). The source, which has an unprecedentedly low uncertainty, will enable current calibrations that are consistent with the redefined SI and boost efforts to close the so-called quantum metrology triangle [3].

The new current source is essentially a quantum realization of Ohm’s law, , where is current, is voltage, and is resistance. The electron charge enters because and are each provided by a quantum electrical device whose outputs involve [4]. The voltage source is an array of superconducting Josephson junctions, which, when driven by microwaves at frequency , produces a voltage , where is the Planck constant. The resistance comes from a two-dimensional electron gas that is placed in its th quantum Hall state by a large magnetic field, in which it has a Hall resistance . Ohm’s law for the quantum current then becomes . Since and are known exactly and the uncertainty of is negligibly small, the uncertainty of is limited by such seemingly little things as the “lead resistance” contributed by connecting wires and various sources of random noise.

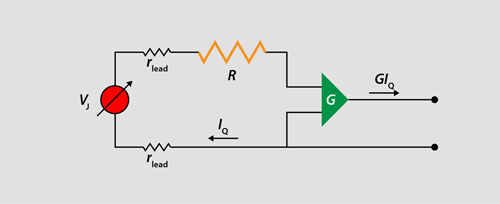

These technical details are, however, the crux of why it’s challenging to make a high-precision quantum current source. To understand the problem, consider a simplified diagram of the device (Fig. 1). Here, a Josephson voltage source connects directly to a conventional resistor whose resistance can be calibrated in terms of the quantum Hall resistance. The output of this circuit is then fed into a conventional current amplifier that provides a variable amount of gain. (An adjustable current for practical calibrations can thereby be achieved by varying the gain and/or the voltage source.) This circuit has two big problems when it comes to producing currents with relative uncertainties below one part in a million. First, the resistance of the leads increases the circuit’s effective resistance by an amount that cannot be determined with high enough accuracy. Second, the gain of even the best conventional amplifier is not sufficiently stable. Poirier and colleagues’ tour de force achievement is realizing a circuit (Fig. 2) that overcomes both hurdles simultaneously.

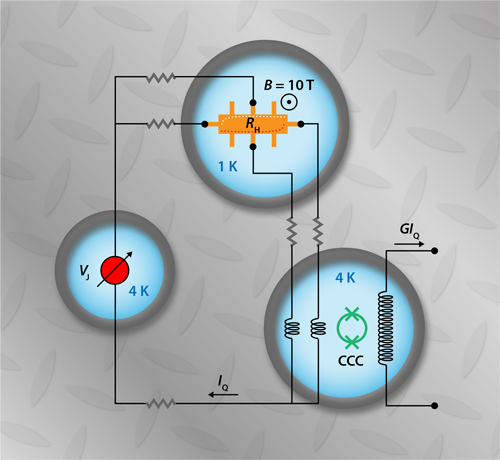

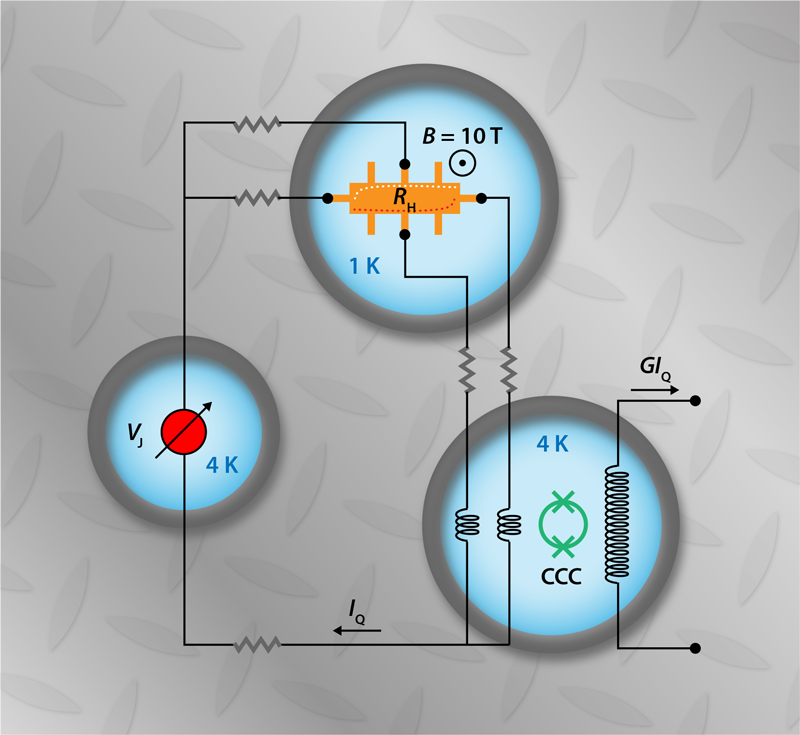

The team addresses the issue of lead resistance by exploiting a unique feature of quantum Hall devices; namely, that they can be wired up such that electrons experience the same electrostatic potential in a lead and along the edge of the device to which it is connected (Fig. 2). This property, which follows from the topologically protected nature of the quantum Hall state [5], reduces the effect of lead resistance dramatically. With lead resistances measured to 1% uncertainty, the French group was able to reduce the leads’ contribution to the uncertainty of the output current to a few parts per billion.

They solve the problem of unstable gain by using an amplifier built from a special type of dc transformer known as a cryogenic current comparator (CCC). In a CCC, superconducting shielding ensures that the ratio of the transformer’s output to input current is precisely the winding ratio of its input and output coils. The device has been a workhorse of electrical metrology for decades, providing gain values of up to 10,000 with part-per-billion uncertainty and excellent stability. Poirier and co-workers optimized their homemade CCC for use in the quantum current source by making several delicate tweaks, such as adding coarse- and fine-gain tunability. Together with the adjustable Josephson voltage source, the CCC allows the output current to range from 1 to 10 with an uncertainty of less than .

Our description does not do justice to the size and complexity of the actual apparatus. Each of the three main elements—the resistor, the voltage source, and the current amplifier—must be cooled to within a few degrees of absolute zero. For practical reasons, the French team did so using a separate cryostat for each element. With the ancillary electronics for controlling each device and the data-acquisition system, the complete setup occupies a laboratory space equal to a typical American two-car garage. They plan to reduce the footprint considerably by placing all three elements in one cryostat. A key step toward this will be to use a quantum Hall device based on graphene that can operate in a smaller magnetic field (potentially as low as 3.5 T instead of 10 T) and at a higher temperature (4 K instead of 1 K) [6].

As a calibration standard, the quantum current source designed by Poirier and colleagues has 100 times lower uncertainty than what is routinely offered by metrology institutes around the world. Not only will it enable calibrations of today’s best commercial ammeters directly in terms of the new SI ampere (based on ), but it will also ensure that metrologists can support future instruments.

The new source will also impact cutting-edge metrology. Groups at several national measurement institutes are pursuing single-electron tunneling (SET) devices that clock the flow of individual electrons at a frequency , thus producing a current in the pA to nA range. Precise comparisons between and a quantum current derived from and would realize a longstanding goal known as the quantum metrology triangle [3]. Showing that the two currents are identical would provide strong evidence for the ideal relations linking , , and to and ; finding a discrepancy would spark a fervent search for the physics that modifies one or more of these relations. The best triangle experiment to date has found no deviation within an uncertainty of [7]. The lower uncertainty offered by the French group’s device promises to extend this test’s precision by at least order of magnitude, but researchers will need to fabricate better SET devices to exploit this potential. If researchers can demonstrate a triangle that is perfect to within 1 part in , they will be even more confident in the foundation for electrical measurements provided by the new SI.

This research is published in Physical Review X.

References

- D. B. Newell, “A More Fundamanetal International System of Units,” Phys. Today 67, No. 7, 35 (2014).

- J. Brun-Picard, S. Djordjevic, D. Leprat, F. Schopfer, and W. Poirier, “Practical Quantum Realization of the Ampere from the Elementary Charge,” Phys. Rev. X 6, 041051 (2016).

- H. Scherer and B. Camarota, “Quantum Metrology Triangle Experiments: A Status Review,” Meas. Sci. Technol. 23, 124010 (2012).

- These devices have been refined over the past 25 years and modern versions routinely achieve ; B. N. Taylor and T. J. Witt, “New International Electrical Reference Standards Based on the Josephson and Quantum Hall Effects,” Metrologia 26, 47 (1989).

- This is the same topological effect for which David Thouless was awarded the 2016 Nobel prize in Physics. The Nobel Prize in Physics 2016.

- R. Ribeiro-Palau et al., “Quantum Hall Resistance Standard in Graphene Devices Under Relaxed Experimental Conditions,” Nature Nanotech. 10, 965 (2015).

- M. W. Keller, N. M. Zimmerman, and A. L. Eichenberger, “Uncertainty Budget for the NIST Electron Counting Capacitance Standard, ECCS-1,” Metrologia 44, 505 (2007).