Directionally Sensitive Magnetoresistance

Magnetoresistance—a resistance induced by a magnetic field—is often associated with magnetic materials. Recent studies have identified a new effect called unidirectional magnetoresistance (UMR), which appears in nonmagnetic materials. The effect is characterized by an increase or decrease in the resistance, depending on the direction in which the current flows. A new experiment has discovered UMR in a surprising place—within the common semiconductor germanium. What’s more, the size of the effect is 100 times larger than in previous cases. The researchers propose a new theory of UMR to explain their results.

UMR was first seen in 2017 in a topological insulator, and a detection of the effect in a two-dimensional electron gas quickly followed. As these systems are not intrinsically magnetic, researchers have inferred that UMR is the result of spin-momentum locking, which is the lining up of electron spins in a direction perpendicular to their momentum. Because of this spin-current connection, UMR could be useful in spintronic devices.

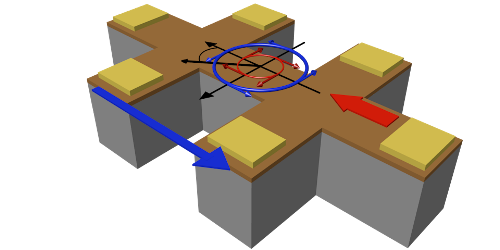

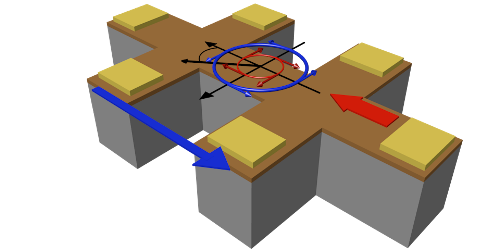

To measure UMR in germanium, Thomas Guillet from Grenoble Alpes University in France and his colleagues grew a layer of germanium along its (111) crystal orientation on a silicon substrate. They ran a current through the layer, while applying an external magnetic field. The measured resistance depended on the current and the field, with the strongest UMR effect occurring when the current was perpendicular to the magnetic field. As an example, a current of 10 A and a field of 1 T produced a 0.5% change in the resistance, compared to a 0.002% change in previously observed UMR materials. To explain this relatively large response, the team proposes that the Rashba effect—a well-known splitting in the bands associated with up and down spins—generates spin-momentum locking in the subsurface states of germanium.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Michael Schirber

Michael Schirber is a Corresponding Editor for Physics based in Lyon, France