Bacteria Never Swim Alone

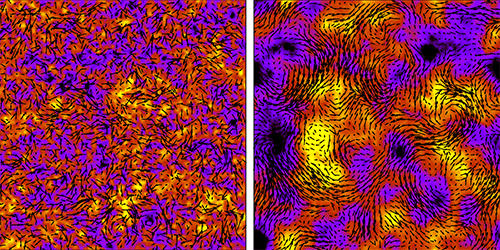

Increase the density of bacteria suspended in a liquid, and the microorganisms will switch from seeming to swim at random to swimming collectively. Eventually they will form large-scale vortices characteristic of turbulent flow (see 28 May 2013 Viewpoint). Researchers simulating this transition to turbulence have now shown how the correlated swimming of many bacteria builds up as the transition is approached. Surprisingly, they find that the correlations affect the motion of bacteria even when they are far apart and appear to swim erratically.

Bacteria in a liquid suspension induce flows in the surrounding fluid as they swim. In sufficiently dense suspensions, the cells “feel” these flows from nearby bacteria, causing the correlated motion of neighboring swimmers. Joakim Stenhammar, from Lund University in Sweden, and colleagues succeeded in describing such fluid-mediated interactions and their dependence on bacteria density by carrying out simulations of bacterial suspensions with varying numbers of cells (up to 4 million) and various densities. They also developed a kinetic theory for the bacteria’s motion.

In simulations of sparse suspensions, the bacteria appeared to move at random. But the team nonetheless discerned correlations between the bacteria that were transmitted via the fluid. Ramping up the density, the team observed and, for the first time, quantified the strength of the fluid-mediated interactions. Up to now, the expectation has been that correlations turn on suddenly at a certain density. But Stenhammar and colleagues’ theory and simulations are more consistent with correlations that increase steadily. The researchers also found that the correlations responsible for collective motion are governed almost entirely by mutual rotations of the bacteria.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Katherine Wright

Katherine Wright is a Contributing Editor for Physics.