Seeking Stability in a Relativistic Fluid

The theory of fluid dynamics has been successful in many areas of fundamental and applied sciences, describing fluids from dilute gases, such as air, to liquids, such as water. For most nonrelativistic fluids, the theory takes the form of the celebrated Navier-Stokes equation. However, fundamental problems arise when extending these equations to relativistic fluids. Such extensions typically imply paradoxes—for instance, thermodynamic states of the systems can appear stable or unstable to observers in different frames of reference. These problems hinder the description of the dynamics of important fluid systems, such as neutron-rich matter in neutron star mergers or the quark-gluon plasma produced in heavy-ion collisions. Now Lorenzo Gavassino of the Polish Academy of Sciences establishes a simple criterion to determine whether a given relativistic-fluid-dynamical theory is associated with paradoxical instabilities [1]: if a theory violates causality, it will also generate such instabilities. The result will provide important guidance in the search for a viable theory for relativistic fluids.

In the past two decades, many fluid-dynamical theories have been developed to address the nonphysical aspects of extensions of the Navier-Stokes theory [2–7]. The most famous, derived by Israel and Stewart, is applied extensively in nuclear physics [6]. All these efforts were based on the premise that a consistent theory of relativistic fluid dynamics must be causal in order to be stable. This assumption was suggested by many stability analyses and implied that causality and stability are intimately related: if a theory allows for signals propagating faster than the speed of light—in other words, if it violates causality—the analyses typically found observer-dependent instabilities. For example, perturbing a viscous fluid (in equilibrium) at rest leads to stable, exponentially decaying modes—the typical behavior expected for a dissipative fluid. But perturbing the same fluid in motion may lead to unstable, exponentially growing modes [8–10].

For a long time, this counterintuitive causality-stability link of relativistic fluid dynamics was not well understood, even from a qualitative point of view. Gavassino’s work sheds light on this complicated problem and provides intuitive and surprisingly simple answers to the apparent paradoxes. Using concepts from relativity, he connects the causality of an arbitrary fluid-dynamical theory to its stability in any frame of reference.

The main result of this paper is the general proof that if a casual dissipative theory is stable in one frame of reference, it will also be stable in any other frame of reference. This conclusion considerably simplifies the task of analyzing the stability of dissipative fluid-dynamical theories. Prior to this work, for a theory of fluid dynamics to be consistent, its stability had to be proved in all possible reference frames—a cumbersome task that requires complicated and, often, numerical calculations. On the other hand, testing causality and stability of a fluid in a single frame is considerably simpler and can be accomplished analytically.

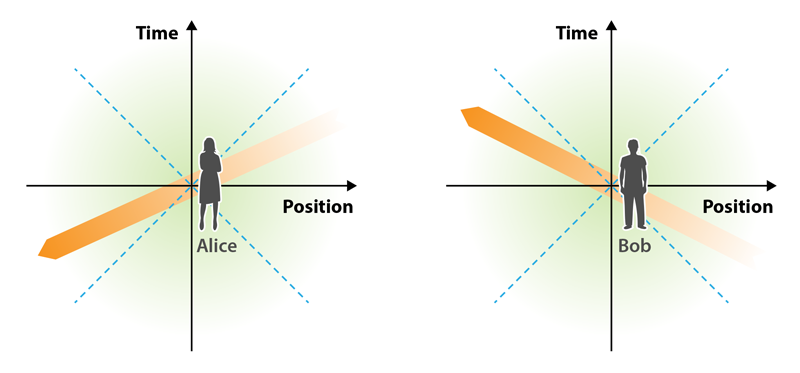

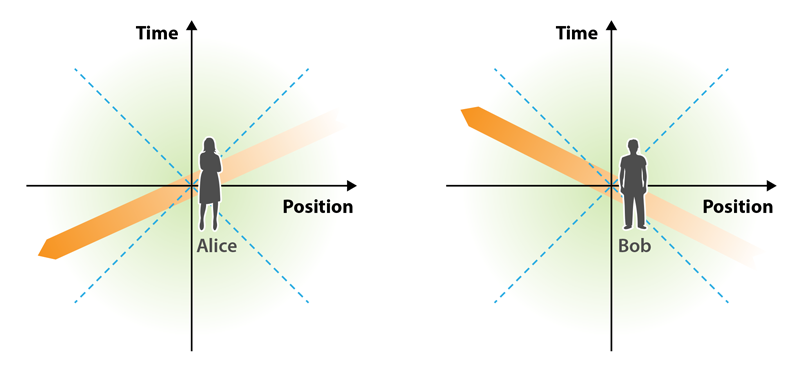

This paper also provides a simple and intuitive explanation for why different observers can disagree about the linear stability of a given dissipative theory and for why this only occurs if the corresponding theory violates causality. Gavassino constructs his answer by investigating whether different observers agree on whether a perturbation is growing or decaying in a fluid with respect to the observer’s own time (Fig. 1). He considers a perturbation that moves faster than light and whose energy is gradually dissipated—the perturbation amplitude decays over time from the perspective of a given observer. Since the perturbation is superluminal, it is traveling along a path that falls outside of the light cone—the region that describes how a flash of light spreads out through spacetime. The perturbation therefore links causally disconnected spacetime points that can be chronologically inverted in a relativistic frame transformation, that is, the part of this path that happens “earlier” and the part that happens “later” may be inverted depending on the observer’s frame of reference. The perturbation’s amplitude, which decays in the first observer’s frame, is then seen to increase from the point of view of another observer. Thus, the violation of causality can transform dissipative behavior into a growing instability simply by performing a reference-frame transformation.

This clever argument generally explains why dissipative theories that are not causal won’t ever provide a viable description of relativistic fluids, offering a simple test that any candidate for a theory of relativistic fluid dynamics must pass. A “correct” theory of relativistic fluid dynamics will be very different from its nonrelativistic counterparts. As new observations of astrophysical objects, including black holes and neutron star mergers, provide increasingly detailed and precise data, the need for a reliable relativistic-fluid-dynamical theory becomes more pressing. Most of these astrophysical processes are currently modeled using equations that do not include dissipation. Given the relevance of the topic for relativistic astrophysics as well as for heavy-ion collision simulations, Gavassino’s work will certainly rekindle interest in how best to understand the role of causality in hydrodynamics.

References

- L. Gavassino, “Can we make sense of dissipation without causality?” Phys. Rev. X 12, 041001 (2022).

- L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz, Fluid Mechanics: Volume 6, 2nd edition, edited by L. D. Landau and E. M. Lifshitz (Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 1987)[Amazon][WorldCat].

- G. S. Denicol et al., “Stability and causality in relativistic dissipative hydrodynamics,” J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 35, 115102 (2008).

- S. Pu et al., “Does stability of relativistic dissipative fluid dynamics imply causality?” Phys. Rev. D 81, 114039 (2010).

- W. A Hiscock and L. Lindblom, “Stability and causality in dissipative relativistic fluids,” Ann. Phys. 151, 466 (1983).

- W. Israel and J. M. Stewart, “Transient relativistic thermodynamics and kinetic theory,” Ann. Phys. 118, 341 (1979).

- I. Müller, “Speeds of propagation in classical and relativistic extended thermodynamics,” Living Rev. Relativ. 2 (1999).

- G. Denicol and D. H. Rischke, Microscopic Foundations of Relativistic Fluid Dynamics, Lecture Notes in Physics Vol. 990 (Springer, Cham, 2021)[Amazon][WorldCat].

- C. Eckart, “The thermodynamics of irreversible processes. III. Relativistic theory of the simple fluid,” Phys. Rev. 58, 919 (1940).

- W. A. Hiscock and L. Lindblom, “Generic instabilities in first-order dissipative relativistic fluid theories,” Phys. Rev. D 31, 725 (1985).