How Order Emerges in Bendy Beam Bunches

When a collection of thin elastic beams—such as toothbrush bristles or grass—is compressed vertically, the individual elements will buckle and bump into one another, forming patterns. Experiments and numerical simulations now show that basic geometry controls how order emerges in these patterns [1]. The results could be useful for designing flexible materials and for understanding interactions among flexible structures in nature, such as DNA strands in cells.

Studies of bending and buckling have often focused on the behavior of a single membrane, such as a thin disc of polystyrene fabric, a sheet of crumpled paper, or even a bell pepper. But few models have tackled the dynamics of a group of many elastic objects.

Applied mathematician Ousmane Kodio of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was inspired to tackle the problem of order in elastic beams when he saw the gills of a dried mushroom bending and forming patterns under compression. “We really wanted to understand how a collection of beams interacts and [how the interactions] lead to order,” Kodio says.

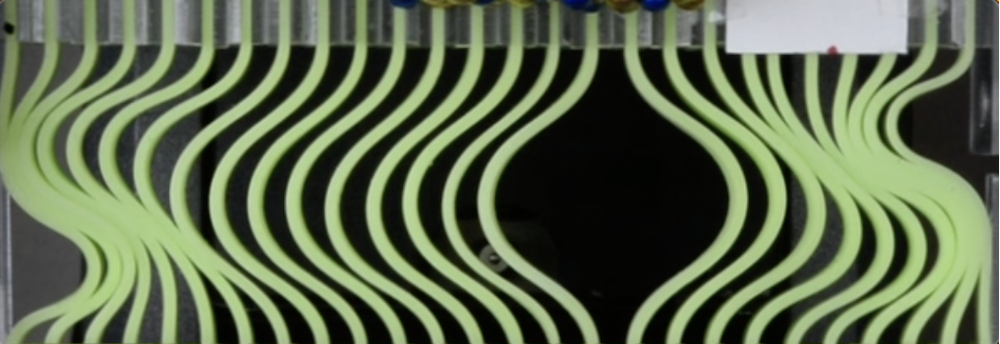

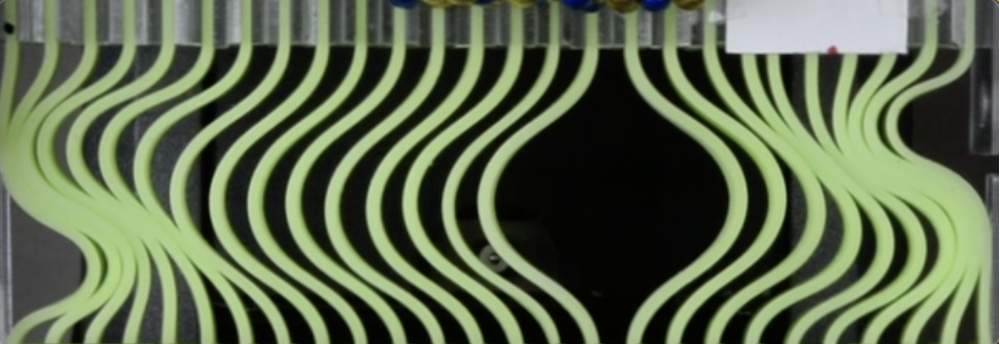

To investigate the emergence of order, Kodio and his colleagues fixed twenty-six 1.6-mm-thick, 54-mm-tall, flexible plastic beams vertically between two horizontal plates. The beams were ribbon-shaped and could buckle only to the right or to the left. To ensure randomness, at the start of each experimental run, the researchers gave each beam a small initial right or left bias determined by flipping a coin. Then they squeezed the plates together, which caused the beams to bend and come into contact with one another.

To measure the order at any point during compression, the researchers counted the number of beams that buckled in each direction. They assigned a number to each beam: −1 if it bent to the left and +1 if it bent to the right. By taking the average of these numbers and then the absolute value, they defined a measure of the order that could range from 0, corresponding to the beams bending in random directions, to 1, corresponding to all beams bending in the same direction.

Kodio and his colleagues also conducted numerical simulations in which they varied several parameters, increasing the number of beams to 300, varying the spacing between beams, and changing the friction coefficient. Contrary to expectations, none of these changes had a substantial effect on the emergence of order.

Order increased with compression and seemed to depend mainly on one factor: the ratio of the uncompressed beam height to the compressed beam height. The researchers also developed a mathematical model that allowed them to predict how much order there would be at a given level of compression. For example, the model correctly predicts that when beams are compressed to about 30% of their height, they have an order of 0.6—a majority bend in the same direction.

In both experiments and simulations, the researchers observed a set of phenomena that seemed to govern the emergence of order. “Clumps” are areas where many beams press together, while “holes” are areas where beams open up a gap between neighbors buckling in opposite directions. “Whenever a clump and a hole touch, the clump rushes into the hole,” says team member and Boston University graduate student Arman Guerra. The researchers playfully call these events “clump-hole annihilation,” and they found that the order of the system can also be described by the number of clumps and holes that persist, since both prevent beams from aligning.

The researchers are clear about the limitations of these experiments. For example, they did not consider cases of extremely dense packing, where friction might grow more important. They also did not investigate more complex beam ordering scenarios where only one end of each elastic beam is fixed, and it can move in multiple directions, such as hair on a scalp.

Harold Park, a professor of mechanical engineering at Boston University who was not involved in the research, suggests that future experiments should incorporate tunable friction between beams to confirm more of the predictions of the numerical simulations. But Park says that the lack of adjustable friction in the current experiments is justified by the novelty of the approach. Dominic Vella, an applied mathematician at the University of Oxford, UK, was impressed by the way the team developed a simple strategy. “It’s a problem that you look at and think, ‘Oh, goodness, how are you going to say anything useful about that,’” he says. “And then you realize that geometry has such a central role.”

–Dan Garisto

Dan Garisto is a science journalist based in New York City.

References

- A. Guerra et al., “Self-ordering of buckling, bending, and bumping beams,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 148201 (2023).